There’s an interesting piece of history hiding in the outer reaches of the GDA (Greater Dodgeville Area, loosely defined as any place I can reach by bike) just north of Newmarket: the scattered remnants of the Newmarket Canal.

This never-finished canal was to be a southerly branch of the Trent-Severn canal from Lake Simcoe to Aurora via the Holland River. This was not a trivial undertaking for many reasons, not the least of which was that there just wasn’t enough water in the river to operate a canal. The initial plan for the canal called for reservoirs to be fed by water diverted from Lake Wilcox, the source of the Humber River. That plan was later shelved as being too expensive and politically unpopular, and was replaced by a scheme to pump the necessary water uphill from Lake Simcoe to the top of the Oak Ridges Moraine at Aurora.

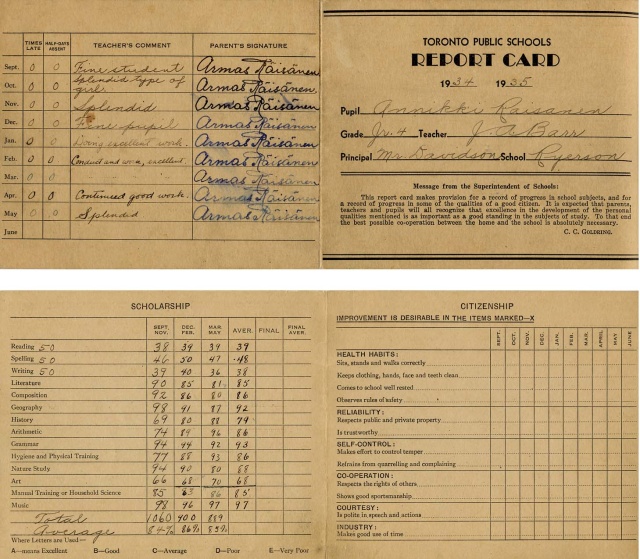

Work on the canal was to be done in three stages: the first required that the river be dredged from Lake Simcoe to Holland Landing. The second required three locks to be built between Holland Landing and Newmarket (the second of those locks is pictured above). The final phase, from Newmarket to Aurora, would require an additional five or six locks depending on the final route, which still hadn’t been finalized when construction began.

Even as the work on the canal began in 1906 and continued for five years, there was still no clear plan for keeping enough water in the canal to keep it navigable during any period of the year outside the spring thaw. Increasing public opposition, escalating costs, and a change in government ultimately doomed the project in 1912 after years of political shenanigans, interference, and scandals that would make most modern politicians blanche. At that point, most of the work on the canal through Holland Landing and up to Newmarket had been completed. The three lock structures and the base of one swing bridge that had been built before the project was called off still stand along the east branch of the Holland River north of Newmarket.

James T. Angus’s comprehensive book, A Respectable Ditch: A History of the Trent-Severn Waterway 1833–1920, details the tortuous political and physical paths of the entire project’s 90 years of debate, design, and construction. It devotes a chapter to the Newmarket Canal debacle and is well worth reading.

This was at least the second planned canal along this route. The other would have gone straight through the Oak Ridges Moraine and connected to Lake Ontario via the Humber River.

I first visited two of the abandoned lock structures almost 20 years ago, shortly after learning about the Newmarket Canal in Ron Brown‘s excellent guidebook, 50 Unusual Things to See in Ontario. I finally visited the third lock and the swing bridge just this past September.

Looking back now, 50 Unusual Things was probably what set me off on my habit of exploring the GDA and finding unusual sights and abandoned bits of the city. Damn you, Ron Brown!

My most recent cycling visit to the canal was on Saturday, during which I was trapped under a sheltering bridge for an hour and a half by that big storm that whipped across southern Ontario. I eventually called Risa to rescue me with the car after giving up hope that the lightning, rain, and wind would let up in time for me to get back home at a reasonable hour.

The irony here is that I was stuck within spitting distance of the East Gwillimbury GO station. I could easily have gone home by train, but the next one was 36 hours away on Monday morning and I wouldn’t have been able to take my bike on it. Hello GO? Weekend service, please.

More pictures below the fold.

Read More …